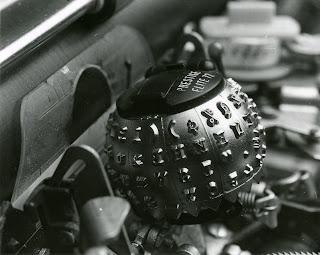

Muybridge and the Typewriter - A Photographic Motion Study on the IBM Selectric

I decided to make this header photo extra large as it is itself, the subject of this article. Before we delve into this thing I created, I figured it would do some good to explain the origin of the idea, which is twofold. The very first motion picture was released in 1878 by Eadweard Muybridge, and featured a running horse. The film was created on glass plate negatives with specialty cameras with gravity-fed shutters designed by Muybridge himself. The goal was, in short, to examine things in detail that the eye could not naturally capture. Muybridge was tasked with discovering if and when all four hooves of a horse were off the ground. Over the later parts of his career, Muybridge conducted many other sequence photographic projects which served as a sort of slow-motion analysis.

The second facet of this project's inspiration originates much much later, in the 1960s. IBM had just released the first of the Selectric series electric typewriters, which featured a moving single element that indexed and struck letters faster than the eye could perceive. They showed this off in slow-motion with a high speed camera in an old advertisement.

My goal with this project was to create a motion study of the IBM type element much in the same manner Muybridge would have, and I wanted to conduct it on film.

The Selectric II is a complicated machine, one I have covered in previous articles. My personal machine is by no means the cleanest one around, but it works well enough. For this project, my biggest limitation was not having a high speed camera. In order to capture the detail of the motion, I had to use the IBM hand crank, and turn the OP shaft at small incriments, photographing each time--essentially creating a stop motion animation.

I chose to work this project in film because I wanted the final product to be a contact sheet. There is a certain beauty surrounding a contact sheet that I like, it isn't quite a blank canvas. The closest I could relate it to is a nice base coat. It is a physical object, created entirely without interference, organic and wholly original. The contact sheet is the first moment you get to see all of your images together. You're not worried about detail since they're so small, you are looking mainly at composition. What better way to show a compilation of images than as one large composition?

I pulled out my Nikon F3/T, the only unloaded camera I had at the time, and loaded in a fresh roll of T-Max 100. I also used the Nikkor AFD 60mm Macro lens, and a large diffused studio light shining straight down. The light not only allowed me to stop down to f11 for more depth of field, but it also highlighted the dimension of the type element.

One by one I clicked away each frame. Given the current high prices of film, it felt a little odd to be shooting a single roll in its entirety over the course of just a few minutes. Though in practice it is nearly identical to taking an 8x10 large format photograph. The same surface area of material all for a single composite image.

My first batch of developer was very expired. It is supposed to be crystal clear, not whatever the heck it was. The development itself was a standard process. It took me about a half hour, and another hour to let the film dry before contact printing. My darkroom was a mess, as it had been about a year and a half since I had printed anything. The typewriter world has kept me busy, so much of my photographic work has translated into digital. It felt nice to be back, even just for a short while. My developer had gone bad as was expected, but the fixer was still good. I even, to my surprise, had a brand new box of photo paper waiting for me.

Seeing as the contact would be the final print, I decided to do something I had never done with one before. I added contrast! I chose a number 3 filter, my favorite for black and white, and tacked on another second to my exposure. It isn't always easy to get the little images in the contact to expose just the way you want, so a little bit of post processing (scandalous) helped me out in that regard. Sorry to disappoint all the purists out there.

Very fun, well done!

ReplyDeleteYes, crazy project - but that's exactly why it's fun & interesting :D

ReplyDeleteWow, great work!

ReplyDelete